But inference skills aren’t only about loving to read. They’re also a crucial part of developing learners’ reading comprehension. The ability to infer helps learners to think critically about a text and engage with it academically. Not only does this help learners understand a text, but also helps to improve their reading comprehension skills.

Children begin to make inferences in reading from as early as Year 1, perhaps even earlier. According to the National Curriculum document, good comprehension stems from linguistic knowledge and knowledge of the world around us. Experience of high-quality discussion, along with exposure to a range of texts also helps to develop comprehension skills.

What are inferences?

Making an inference is often referred to as reading between the lines. It is the process of making a guess about something you don’t know for sure, based on the information available.

For example, you see Aidan bite into a piece of fruit and give a delighted smile. From this observation, we can infer that Aidan is enjoying the taste of the fruit.

When we read something, we also make inferences. We use previous knowledge acquired, along with information from the text to draw conclusions, make judgements and interpret the text.

How does making inferences improve reading comprehension?

Making inferences is essential when it comes to successful reading comprehension.

Much of the information we obtain from reading comes from what is implied as opposed to a direct statement of the information.

By making inferences, we are tapping into what we already know from the world around us or from earlier in the text. We then combine this previous knowledge with what we are reading, and the two work in harmony to support us in having a deeper understanding of the text. We are able to infer that which is not outrightly stated.

According to research by Andersen and Pearson (1984), those who are proficient in reading use their prior knowledge as well as textual information to draw conclusions, make critical judgements and form interpretations from the text read. They found that inferences can take the form of conclusions, predictions or new ideas.

When do we make inferences?

As readers, we make lots of inferences as we digest a text. In some cases, we make inferences about specific details. This often involves arriving logically at a theory based on previous or surrounding evidence.

In other cases, we make inferences about the main idea of a piece of text. We may need to infer the main idea of a text if the main idea is not clearly stated. Other instances in which we need to infer the main idea are if:

- The text starts with a question

- The text compares or contrasts two or more things

- Every sentence in the piece of text contains equally specific information

- The text is a satirical piece, or the author uses an ironic tone of voice

Boost reading comprehension on Bedrock

Explicit literacy instruction, powered by a unique deep-learning algorithm.

How do we make inferences?

To get the information we need to make an inference, we can follow five simple steps.

- Read the text

- Read the comprehension question

- List details relevant to the question being asked

- Put the details together

- Decide what these details indicate

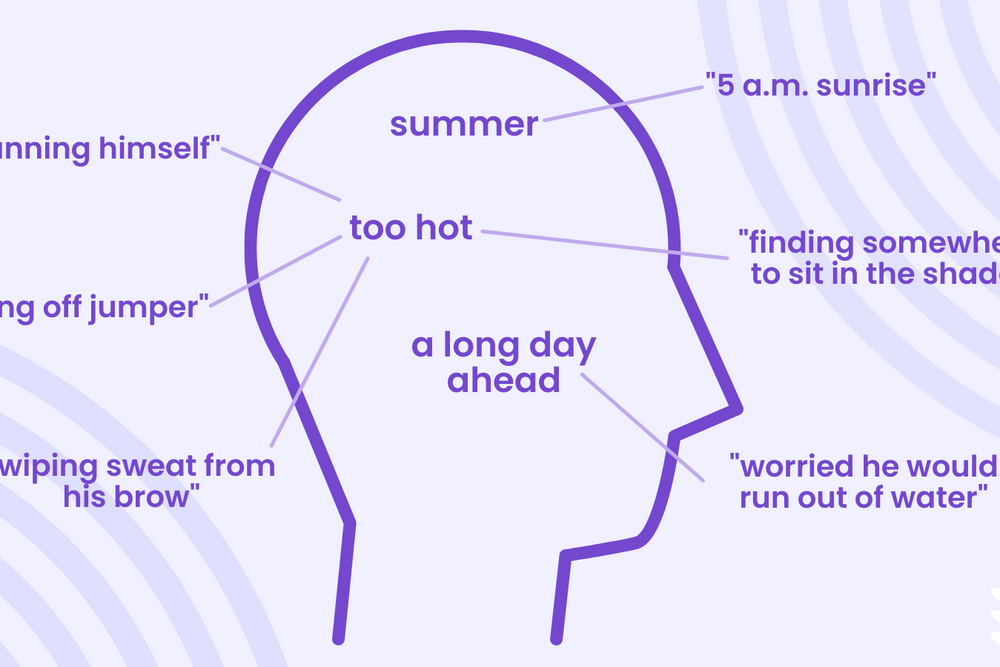

In her book, Chart Sense, Roz Linder uses the silhouette below to depict this process. The details stated outright in the text that is relevant to the question are written outside the silhouette. These details are then pieced together to form inferences which are written inside the silhouette.

The example above demonstrates how the question, “What season is it?” can be answered by inferring using given details in a piece of text.

Two types of inference

There are two kinds of inferences we can make: logical inferences and reason-based inferences.

Logical inference

When we use logical inference, we reach conclusions by going from something specific to something general. We often begin with an observation and then expand this into a general theory or conclusion.

For example, your dog hides as soon as the fireworks begin on Bonfire Night. It does so again on New Year’s Eve when the fireworks start, and then again when the fireworks start on Diwali and Chinese New Year.

From these specific observations, it would be logical to infer the general theory that your dog is afraid of the sound of fireworks going off.

Reason-based inference

Reason-based inferences work the other way around. A reason-based inference starts with a general theory or hypothesis. It then focuses on something specifically observed or stated to prove this theory.

An example of this is, you might have a general theory that the scheduled fireworks display for your neighbourhood will be postponed due to the rain forecast. This is based on your specific knowledge that fireworks can’t perform when it is raining. You have made an inference and come to a conclusion based on reason.

Making inferences using the 5 C's

The spectrum of learning within the classroom, and indeed ‘in real life’, is broad. From those who relish a challenge to those who break out in a cold sweat due to abject doubt in their own ability to successfully complete that challenge. And, of course, there are many other types in between.

As learners, we all learn in different ways. Some thrive in the traditional ‘lecture’ style of learning, while others are more suited to independent reading and learning. Then there are those who excel when working and learning collaboratively.

With this in mind, the 5 C’s framework came to be. This structure teaches the skills and values that will be both necessary and valued in the 21st century.

The Five C’s:

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Creativity

- Critical Thinking

- Character

Collaboration

Through collaboration in the classroom, learners can work together to infer. This engagement may lead to a question, an idea or even draw upon a previous experience that one learner may not have had access to had it not been for collaborating to infer information.

Communication

When learners have the freedom to communicate with one another, they have more exposure to the inference which ultimately leads to the answer to the question. But the focus is on the ‘journey’ to that answer rather than solely the answer itself. This helps that learner add to their ‘tool kit’ for next time.

Creativity

When collaboration and communication are alive and well in the classroom, this often organically leads to creativity. While one child’s life experiences or interpretations of the text might lead to one answer, a different child might infer a whole new meaning. If this inference is based on sound reasoning, then there is every chance both answers are correct.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking also helps with making inferences. The more evidence we gather, and the more thoughtfully and carefully we reason, the sounder our inferences are likely to be. The more textual evidence we can incorporate into our inference, the more likely it is that we have not strayed too far from the meaning intended.

Character

With character in mind when making inferences, students learn how to interpret the emotions and prior actions of a character to predict future actions. This encourages learners to analyse the structure of a text, the semantic fields of the language used within, and the character study itself. In this way, inference combines all the necessary skills of strong reading comprehension.

Boost reading comprehension on Bedrock

Explicit literacy instruction, powered by a unique deep-learning algorithm.

Traits of good inference

According to cognitive psychologist, Professor Daniel Willingham, inference is not a skill that can be improved solely through practice. He suggests inferring is more a trick than a skill. Willingham believes the ability to make a good inference rests on three things:

- Being aware of whether or not you are understanding what you read

- Connecting ideas together

- Having a wide vocabulary and general knowledge to draw on

Building on this then, the traits of a good inference are:

- Integrative: the ability to integrate information previously stated in the text with text currently being read in order to make connections

- Constructive: the ability to draw from general knowledge outside the text to fill in missing details to understand the text in its entirety

It is worth mentioning here, that as learners gain more knowledge and experience of the world around them (and the vocabulary to go with this), this will help them make inferences. They are better equipped to fill in any gaps in the information given and interpret that which is implied by connecting to their own experiences.

It is important to be aware that not all children will have the opportunity at home to develop their knowledge of the world around them, or what they are exposed to may vary significantly from that of their peers. Therefore, learners should be exposed to a broad and varied curriculum, and enriching opportunities as much as possible in their formal learning setting - this is why Bedrock’s original texts are diverse and knowledge-rich, immersing learners in cultural capital from around the world.

Common mistakes when making inferences

There are common mistakes made when making inferences which can lead to key ideas being lost or the wrong meaning being inferred.

1. Not actively reading the text

Reading can be active or passive. With passive reading, you are letting the information fall into your hands. To be able to infer effectively, particularly for the purposes of moving learning along, reading needs to be active. Making annotations and noting any questions as you read can help with this.

2. Not reading out loud when you haven’t understood something

Reading a text out loud (or mouthing it to yourself if you are in a situation that requires silence) can help us to engage with and understand parts of the text we may have missed if we had just let it ‘stay on the page’. Reading aloud can help hone inferences and lead to a more in depth understanding. Performing a text heightens engagement with the events in the text which leads to a more insightful inference.

3. Failing to summarise texts

Summarising a text allows us to consider the text as a whole, as well as specific aspects of the text. In summarising, we are deciding what information is relevant and why. This process forces us to infer information from the text. When making a summary, it is important that we don’t just write or say everything that has happened. We need to engage with the text and infer the key message or meaning.

Examples of texts that encourage inference

There are lots of ways you can work on inference in the classroom. For instance, a show and infer activity, where learners bring in a box of items that say something about them and the class must guess which learners they belong to. They are inferring information about the learners from the items.

Or another activity could be that children are presented with short sentences on the board, and they must make an inference from the given information, for example, ‘The Jensens put their tent, rucksacks and sleeping bags in the boot of the car.’ From the information given, we can infer that the Jensens are going on a camping trip.

This can lead to inferring information from longer pieces of text, for example, using the lyrics of the song ‘How Far I’ll Go’ from the Moana movie as the piece of text:

I've been staring at the edge of the water

'Long as I can remember

Never really knowing why

I wish I could be the perfect daughter

But I come back to the water

No matter how hard I try

Then posing the question, ‘What phrase suggests Moana feels she is a disappointment?’

The learners would read through the text and conclude that it doesn’t clearly state that she feels she is a disappointment at any point, so they’ll need to look a little deeper. They should be able to make the connection that the line ‘I wish I could be the perfect daughter’ indicates Moana’s feeling of wishing to be something she isn’t. They may draw on personal experience of wishing to be something or for something and feelings of disappointment.

Another possible inference activity could be that the children are presented with all the lyrics to this song. They then have to answer the question ‘What is the overall emotion Moana is feeling in this song? Explain your answer.’

In this case, the children are having to digest all the given information from the lyrics and infer the main idea as we mentioned earlier in the article, or in this case the main emotion. When children have actively read the text and considered the evidence, they should be able to piece it together to conclude that the overall emotion Moana is feeling in the song is frustration, or perhaps curiosity. Both answers can be supported using textual evidence.

Bedrock Learning texts that encourage inferencing

Bedrock’s fiction texts don’t just encourage vocabulary improvement - they’re structured to encourage learners to use their reading comprehension skills. This is because vocabulary and reading comprehension work in tandem to improve learners’ literacy, setting them up for success.

One example of a text that uses inferencing is a sneak peek from Block 7’s What a Predicament!

Kevin had decided long ago that humans, especially those related to him, were not his thing. Discussions with his parents were boring and monotonous; they were always asking him to recount every single uninteresting detail about his day. Meanwhile, his siblings never stopped arguing, and the babies never stopped crying. Kevin had been on the verge of running away and never coming back - but that was before Mick came into his life…

If you read the text carefully, you can get an idea of who, or what, Mick is, and why Kevin has brought him into his life, but the only way to know for sure is to encounter this topic on Bedrock Vocabulary - and the mysteries don’t stop there with this story.

Many other texts on Bedrock Learning are just like this one: full of Tier 2 vocabulary, fluent human narration and interesting reading comprehension activities. Not only does this improve learners’ literacy, but it cultivates a love of reading, and that’s a good habit that lasts a lifetime.

Teaching learners to infer and giving them the opportunities and strategies to be able to infer through exposure to a rich curriculum will help them to become more immersed in a text and take their understanding of that text to a deeper level. And who knows? They might even enjoy it…